Newsday 1977 the Search for Buffalo Continues

In recent years, The New York Times has undertaken a groundbreaking initiative to create obituaries for those whose stories deserve to be told, yet were passed over at the time of their death.

Overlooked debuted in March 2018, featuring the stories of 15 remarkable women that are more than well-deserving of historical preservation. It has since been periodically updated and added to, featuring many more obituaries.

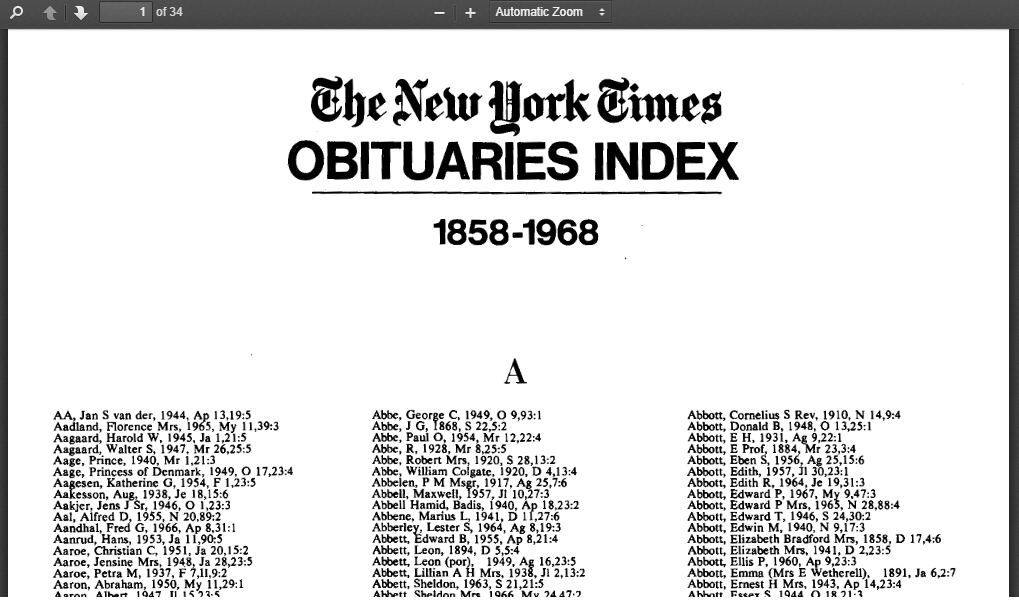

The New York Genealogical and Biographical Society is proud to have contributed to this project by digitizing The New York Times Obituaries Index and optimizing the scanned images for search. This allowed The Times staff to quickly search for names that were included or excluded from coverage in order to select candidates for Overlooked.

The New York Genealogical and Biographical Society is proud to have contributed to this project by digitizing The New York Times Obituaries Index and optimizing the scanned images for search. This allowed The Times staff to quickly search for names that were included or excluded from coverage in order to select candidates for Overlooked.

Obituaries are a fantastic source for researching your family history - if you can find an ancestor's obituary, you have uncovered a potential goldmine of information, including leads for further investigation.

The images of The New York Times Obituaries Index are now available to search or browse on our website in the NYG&B eLibrary. Using this index, a researcher can efficiently find an obituary in the New York Times Article Archive.

While most of our ancestors won't have obituaries in The New York Times, there are plenty of other places to look.

Read on to learn more about Overlooked and The New York Times Obituaries Index, as well as the genealogical value of obituaries and where to search for obituaries from your family tree.

Overlooked and Obituaries in The New York Times

Overlooked aims to take a much-needed revisionist approach to obituaries that have been included in the New York Times over the last 150+ years.

The idea was born when Amisha Padnani joined the Obituaries Desk as the Digital Editor in 2017:

"I was researching an obit for a woman in the tennis world. I discovered the story of Mary Ewing Outerbridge when I stumbled upon a website crediting her with introducing tennis to America. I wondered if she had received a Times obituary when she died in 1886. I checked our digital newspaper archives. She had not. After that, anytime I came across an interesting person who died years ago, I searched our archives for an obit."

influential journalists. Read her obituary.

Padnani soon compiled a list of dozens of fascinating people who were not covered, including some blatant omissions like Sylvia Plath, Charlotte Brontë, and Diane Arbus. Overall, she noticed a clear trend: "Those who didn't get one were, not surprisingly, largely women and people of color."

Later in 2017, Padnani met with The Times's first gender editor, Jessica Bennet. "She agreed that Overlooked was a compelling way to add to the record, and we decided to partner up."

In March 2018, Overlooked launched to well-deserved acclaim, commemorating the lives of 15 remarkable women from history, and has since added dozens more. All obituaries can be read and shared on the interactive Overlooked web page, and The Times will continue to add notable individuals to Overlooked.

Why were historical New York Times obituaries so narrowly focused?

In addition to preserving and sharing these crucial stories, Overlooked raises a question well worth historical consideration: Why were these notable women overlooked in the first place?

William McDonald, the New York Times Obituaries Editor since 2006, reminds us in an article about Overlooked that there is no easy way to decide who does or doesn't get an obituary in the pages of the New York Times.

For The Times, the name of the game is "newsworthiness" - McDonald points out that "it is not our intent to honor the dead; we leave the tributes to the eulogists. We seek only to report deaths and to sum up lives, illuminating why, in our judgment, those lives were significant. The justification for the obituary is in the story it tells."

Even so, readers who peruse The New York Times Obituaries Index and the obituaries themselves will notice the vast majority of subjects are white men.

This will not be a surprise to most genealogists - as we often lament, the records left behind are always a reflection of the world as it was, and so many records and record sets skew their attention to this single segment of the population, leaving many stories untold.

McDonald highlights the historical reality that "the prominent shapers of society back then, those who held (and didn't easily give up) the levers of power, were disproportionately white and male, be they former United States senators or business titans or Hollywood directors."

McDonald suggests that some were overlooked because the paper's selection standards for newsworthiness in decades past unfairly valued the achievements of the mainstream, while others were simply not allowed to make such a mark on society in their own time in the first place.

Overlooked is The Times "acknowledging that many worthy subjects were skipped for generations, for whatever reasons." Read the rest of McDonald's piece, From the Death Desk: Why Most Obituaries Are Still of White Men.

Using The New York Times Obituaries Index

Using The New York Times Obituaries Index

Though they make up a vast majority, the 353,000 names in The New York Times Obituaries Index are not exclusively white men.

McDonald comments that "there were, of course, women who crashed glass ceilings, blacks and Native Americans and people of Asian heritage who pushed through "whites only" barriers. And their stories have been told in the obituary pages over many decades."

Apart from genealogy, historians and social scientists will find this index to be a useful tool for their research.

If one of your ancestors was given an obituary in The Times, this index will help you locate it quickly. The index is organized alphabetically by last name - the digital collection exists as a series of fully-searchable, high-quality PDF files.

To allow the files to load quickly for all users, we have broken up this 1,100+ page file alphabetically.

The collection includes all the names entered under the heading "Deaths" in the issues of The New York Times Index from September 1858 through December 1968.

Each entry includes the following information for each obituary:

- Name of the deceased (as well as title, pseudonym, or nickname if any)

- Year

- Date

- Section (if any)

- Page and column

Once an entry is found, researchers may locate the obituary in the New York Times Article Archive. Visit The New York Times Obituaries Index in the NYG&B eLibrary.

If your ancestor isn't in the index, don't be disappointed - there are plenty of other sources to search for your ancestor's obituary. Read on for some suggestions.

Obituaries and Genealogy

Death notices and obituaries have been appearing in newspapers since the earliest days of newsprint.

These sources can be invaluable to a family history researcher, partly due to the fact that the writer is not limited by specific fields like those found on official forms - an obituary can contain any kind of information on your ancestor.

For this reason, obituaries can vary greatly in their depth, ranging from a one or two-line death notice to an elaborate biographical sketch.

What you can learn from an obituary

In many cases, obituaries are the only complete sketch of an ancestor's life that we will find in our research - apart from the genealogical information within, an ancestor's obituary itself is a valuable life artifact to preserve.

Depending on the specific obituary, a researcher may find:

- Exact place of birth (a major breakthrough for an immigrant ancestor)

- Names and details of parents, spouses, and children

- Information on career, marriage, and circumstances of death

- Notable accomplishments, events, or stories from the subject's life

These would all be very exciting discoveries to make, but researchers should take caution when using sources like obituaries.

Important caveats

One important thing to consider when analyzing an obituary is that it is considered a derivative source - the writer is usually far removed (often several degrees removed) from the actual events they're describing.

For this reason,obituaries should not be used as sole, definitive proof of any genealogical event.

Of course, this does not mean they have no value to the family history researcher - on the contrary, they are excellent leads for further research. A deep obituary will often contain crucial clues that will help you find definitive proof of the events mentioned in the narrative.

So when you find an ancestor's obituary, rejoice, save the original document or image, but keep researching!

Other Obituary Sources

For most family history researchers, there are two good places to begin looking for an ancestor's obituary - the newspapers that served the area they died in, as well as the newspapers that served the town in which your ancestor grew up or lived for an extended period of time.

One challenge in finding obituaries is that they're mainly found in newspapers (although it's important to note that they can also be found in funeral home records, periodicals, local histories, and other similar publications) - it's rare to find a resource like The New York Times Obituary Index, which specifically indexes only the obituaries out of entire issues of newspapers.

According to the FamilySearch wiki, obituaries have only recently begun to be indexed online, and many obituary indexes only date from the late 1960s or 1970s.

But don't let that discourage you - there are plenty of preserved and digitized newspapers that include obituaries.

Helpful tips for finding your ancestor's obituary

There are several pieces of information that will help greatly in locating an ancestor's obituary. Here are three important ones:

- The approximate place of death

- The approximate date of death

- The name(s) of places your ancestor had deep ties to

This last one could include a hometown where your ancestor grew up or another community that your ancestor lived in for an extended period of time. It's not uncommon for local newspapers to mention stories related to former residents, including marriages and deaths.

Other information, like names of other family relations, will help you confirm you have the correct individual.

Once you have the above information, find a publication that was active at the time of your ancestor's death that covers a relevant location. Once excellent resource for this comes from the Library of Congress.

Their Chronicling America, Historic American Newspapers collection contains many digitized and searchable newspapers but also contains a U.S. Newspaper director, 1690 - Present. This database contains a huge list of newspapers published in the United States since 1690 and can help you determine what titles exist for a place and time, along with tips for accessing preserved issues.

You may also need to perform some general internet searches related to the town or county you're looking for coverage of. For more tips, see the free NYG&B guide to Online New York Newspapers.

Once you have found a good candidate paper, the searching begins - if the paper you're using has been digitized and OCR applied, begin with a surname search.

If you're working with microfilm, or with unsearchable digital images, don't give up!

With an approximate death date, browsing through issues is well worth the time - you may be able to pick up a pattern in where newspapers published obituaries within each issue, making your search easier.

Other Sources for Death Records

The unfortunate truth is that not all of our ancestors had obituaries published at all. Although the search is well worth the time, we may need to eventually accept that an obituary cannot be found or may have never been created in the first place.

The good news is there are many other options to find records related to death.

Death certificates

A death certificate is one of the first records you should search for, even before an obituary - the information found on a death certificate is generally reliable (though the informant - whoever provided the information - should always be carefully considered) and can help locate other records. Read our blog, Why you need to have your ancestor's death certificate for more details.

In general, death certificates are most possible to find for New York State after about 1880, though this varies greatly depending on the locality. Researchers should use a death index to find the official death certificate number, and use that to request a copy of the record. Read our guide to Finding New York State Birth, Marriage, and Death Records for detailed information on locating death certificates from the various regions and time periods in New York State history.

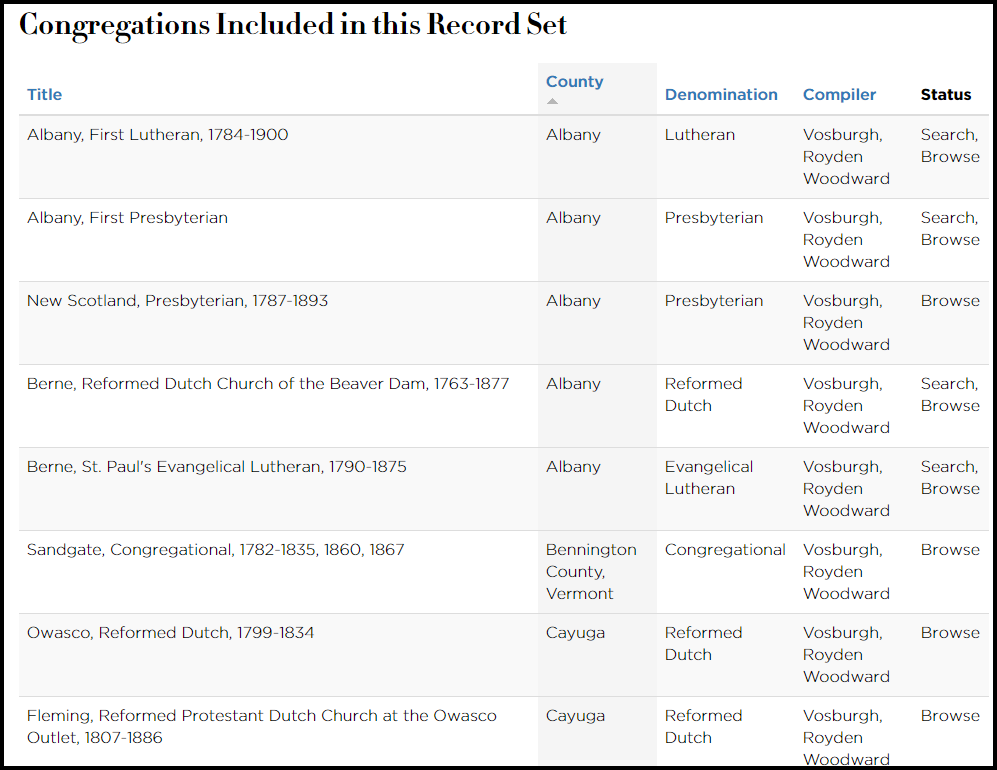

congregations from all over New York State.

Religious records

Because of the complexity surrounding New York State vital records, researchers - especially those investigating families before 1880 - often seek substitute death records when no official state certificate is available.

Before the mid-1800s, many localities in New York State viewed the task of collecting information on birth, marriage, and death to be a function of the Church.

Therefore, religious records often hold key information that wasn't recorded by the state.

Many sets of religious records have been preserved and are being digitized - including recent releases of long-sought-after Catholic Church records.

The NYG&B also has a large collection of New York State Religious Records. We recommend reading our article on using religious records as vital record substitutes.

Other types of records, including probate court records, may provide genealogically relevant information generated by an ancestor's passing.

We hope we have provided a useful overview of using obituaries in genealogy research, the exciting new Overlooked project from The New York Times, and some helpful tips for locating obituaries and other death records.

Let us know if you have any other suggestions to share in the comments!

About the New York Genealogical and Biographical Society

back-to-back Awards of Excellence from

the National Genealogical Society

in 2016 and 2017.

Since 1869, the NYG&B's mission has been to help our thousands of worldwide members discover their family's New York story, and there has never been a better time to join.

The cost of an Individual Annual Membership is less than six dollars a month, and includes the following benefits:

- Access to over 50 exclusive digital record sets covering the entire state of New York, including the fully searchable archives of The Record.

- A complimentary subscription to all of Findmypast's North American records, as well as U.K. and Irish Census records.

- Access to hundreds of expert-authored Knowledge Base articles and webinars to help you navigate the tricky New York research landscape.

- Exclusive discounts and advanced access to conferences, seminars, workshops and lectures to learn more about researching people and places across New York State.

To learn more or join us, please visit our member benefits page.

Read More

-

NYG&B Labs releases The Record map search

-

Eleven ways to use the NYG&B website to improve your skills and find ancestors

-

Surprising facts about immigration to New York

-

Finding Birth, Marriage, and Death Records in New York State

cummingschmervaske1954.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.newyorkfamilyhistory.org/blog/find-your-ancestors-obituary-new-york-times-and-other-sources

0 Response to "Newsday 1977 the Search for Buffalo Continues"

Post a Comment